Why Are ‘First-of-Its-Kind’ Aircraft Challenging to Introduce in India?

India’s difficulty in inducting globally proven business aircraft stems from regulatory complexity and ecosystem readiness challenges which slow the entry of first-of-its-kind aircraft despite strong operator demand

| By SANJEEV CHOUDHARY, VICE PRESIDENT – AIRCRAFT SALES (SOUTH ASIA) AT JETHQ |

India today presents a paradox in business aviation. On one hand, it has a mature civil aviation regulator, experienced operators, globally trained pilots, and increasingly capable maz̄intenance organisations. On the other hand, several modern and proven business aircraft—successfully operating across North America, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia—remain conspicuously absent from Indian skies. This is particularly true for aircraft that are ‘first-of-its-kind’ in India, despite having long and well-established global service records.

UNDERSTANDING THE ‘FIRST-OF-ITS-KIND’ CHALLENGE

In the Indian context, a ‘first-of-its-kind’ aircraft does not imply a new or experimental design. Rather, it refers to an aircraft model that has not previously been registered or operated in India, even though it may have been certified by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) or the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) and may have been in active global service for many years.

Examples illustrate this anomaly clearly. The Cessna Citation Latitude, certified in 2015, has more than 450 aircraft flying worldwide, yet none operate in India. Similarly, the Gulfstream G280 has been in service since 2012, with over 300 aircraft operating globally, but not a single example is registered in India. These are not niche aircraft; they are mainstream platforms with proven safety records and robust global support ecosystems.

TYPE CERTIFICATION ACCEPTANCE AND REGULATORY FAMILIARITY

One of the primary hurdles lies in the acceptance of type certification by the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA). While India recognises FAA and EASA certifications in principle, the practical process of validation often involves additional documentation, internal assessments, and technical familiarisation. This process is essential from a safety oversight perspective, but it can become time-consuming and costly when applied to aircraft that already have extensive global operational histories.

ONE OF THE PRIMARY HURDLES LIES IN THE ACCEPTANCE OF TYPE CERTIFICATION BY THE DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF CIVIL AVIATION (DGCA)

Is there scope for India to simplify and accelerate its validation process—without compromising safety—for aircraft that have already undergone rigorous certification by established global regulators and have a proven operational track record? This is not an argument for dilution of safety standards, but for proportionality and efficiency aligned with global best practices.

TRAINING REQUIREMENTS FOR REGULATORS AND OVERSIGHT AGENCIES

For any new aircraft type, the regulator must ensure that it can effectively oversee operations and continuing airworthiness. This requires training flight operations inspectors, airworthiness inspectors, and design directorate personnel. Such training often involves overseas travel to OEM facilities or approved simulator centres, with associated costs and scheduling challenges.

In practice, these costs are frequently borne by the operator or the OEM, particularly when only one aircraft is being inducted. For a single pre-owned aircraft, this can render the entire acquisition commercially unattractive, even before operational considerations are addressed.

MRO READINESS AND THE INVESTMENT DILEMMA

Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul (MRO) organisations form a critical pillar of the aviation ecosystem. Introducing a new aircraft type requires investment in tooling, ground support equipment, spare parts provisioning, and training of Aircraft Maintenance Engineers (AMEs). These investments are capitalintensive and difficult to justify without assurance of fleet depth.

As a result, MROs are often reluctant to commit resources until an aircraft is firmly inducted, while regulators seek evidence of maintenance capability before granting approvals. This circular dependency creates a classic chicken-and-egg situation that stalls progress.

HUMAN CAPITAL CONSTRAINTS: PILOTS AND ENGINEERS

Pilot induction adds another layer of complexity. Even after completing type-rating training, pilots typically require supervised operating experience before being released as Captains. For a new aircraft type, this often necessitates bringing in foreign instructor pilots, which involves visa processing, security clearances, and significant cost escalation.

Similarly, engineers trained in anticipation of aircraft induction risk losing currency if the process is delayed. This creates additional reluctance for early investment in skills development.

INDIA’S PRE-OWNED AIRCRAFT MARKET REALITY

India is predominantly a pre-owned aircraft market. Buyers prioritise capital efficiency, faster availability, and lower depreciation exposure. While this market reality aligns well with operator needs, it does not always align with OEM incentives, which are naturally focused on new aircraft sales.

However, once a model is established through even a small pre-owned fleet, buyer confidence improves, support infrastructure develops, and the market becomes more receptive to new aircraft of the same type.

THE STRATEGIC ROLE OF OEMS IN ECOSYSTEM CREATION

OEMs can play a transformative role in addressing the first-of-its-kind challenge. By proactively supporting the induction of pre-owned aircraft— through regulatory engagement, documentation support, training facilitation, and coordination with local MROs—OEMs can accelerate ecosystem development.

Such involvement should be viewed as a proportionate strategic investment rather than a cost burden. The long-term beneficiaries are the OEMs themselves, through increased aftermarket revenue, expanded market share, and improved prospects for future new-aircraft sales.

CONCLUSION: A COORDINATION CHALLENGE, NOT A CAPABILITY GAP

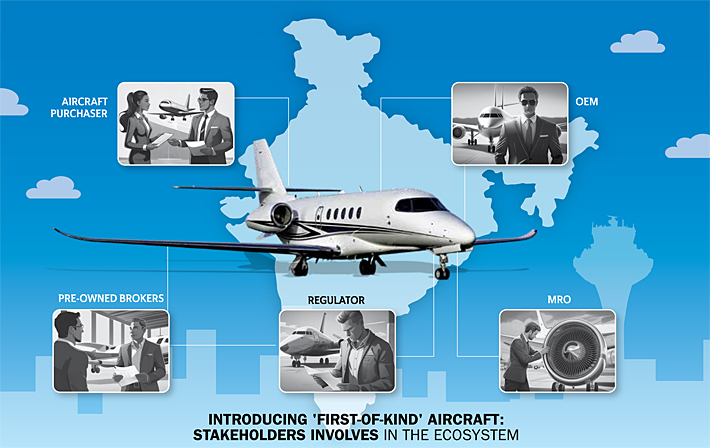

The challenges associated with introducing first-of-its-kind aircraft in India are not rooted in a lack of capability or commitment to safety. They arise from fragmented responsibilities, misaligned incentives, and the absence of a coordinated induction framework.

With structured collaboration between regulators, OEMs, MROs, and operators—and with proportionate, risk-based validation pathways—India can enable faster, safer, and more cost-effective induction of globally proven aircraft. A country renowned for innovation and engineering excellence can certainly design solutions that allow its business aviation community to benefit from modern technology without compromising regulatory integrity.

Sanjeev Choudhary is a senior business aviation professional, with over 20 years of experience, spanning aircraft sales, market entry, and fleet advisory across helicopters and fixedwing aircraft.