INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

The insightful articles, inspiring narrations and analytical perspectives presented by the Editorial Team, establish an alluring connect with the reader. My compliments and best wishes to SP Guide Publications.

"Over the past 60 years, the growth of SP Guide Publications has mirrored the rising stature of Indian Navy. Its well-researched and informative magazines on Defence and Aerospace sector have served to shape an educated opinion of our military personnel, policy makers and the public alike. I wish SP's Publication team continued success, fair winds and following seas in all future endeavour!"

Since, its inception in 1964, SP Guide Publications has consistently demonstrated commitment to high-quality journalism in the aerospace and defence sectors, earning a well-deserved reputation as Asia's largest media house in this domain. I wish SP Guide Publications continued success in its pursuit of excellence.

- The layered Air Defence systems that worked superbly, the key element of Operation Sindoor

- Operation Sindoor | Day 2 DGMOs Briefing

- Operation Sindoor: Resolute yet Restrained

- India's Operation Sindoor Sends a Clear Message to Terror and the World – ‘ZERO TOLERANCE’

- Japan and India set forth a defence cooperation consultancy framework, talks on tank and jet engines

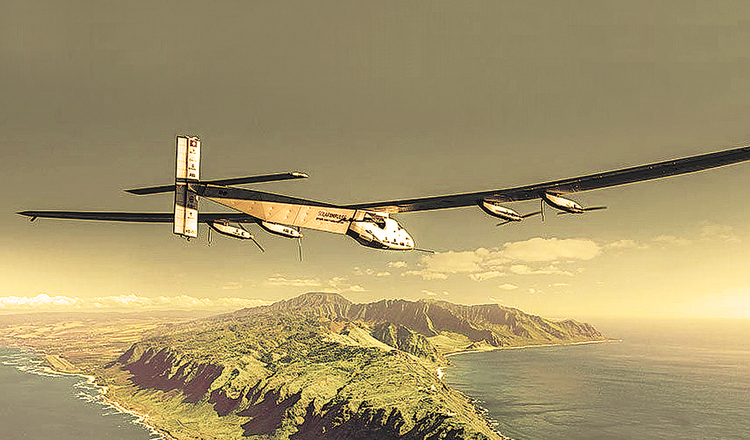

Solar Implulse 2: High on Sunlight

While Solar Impulse’s ability to fly while the sun shone was undoubted, its batteries had to store enough energy to keep the four propellers spinning through the dark night-time hours

On July 26, 2016, Solar Impulse 2 landed in Abu Dhabi to cheering crowds. After 14 months of travel and 550 hours in the air, the Swiss long-range experimental solar-powered aircraft had accomplished what many experts had deemed impossible: flying 40,000 km around the Earth – including over the Pacific and Atlantic oceans – without a drop of liquid fuel. Flown alternately by Swiss engineer and businessman André Borschberg, and Swiss psychiatrist and balloonist Bertrand Piccard, it completed the first circumnavigation of the Earth by a piloted fixed-wing aircraft using only the sun’s vibrant rays to power its four electric motors.

The idea had occurred to Piccard after he made the first, non-stop, round-the-world flight in a balloon in 1999. His Breitling Orbiter 3 balloon only just managed to reach its destination, landing with virtually no reserves of the propane gas it had been burning to remain airborne. But aviation industry insiders said Piccard’s solar plane was an impossible dream because, to have enough solar panels, it would need to be massive, yet extremely light. However, his idea was enthusiastically received by Borschberg, who had trained as a pilot in the Swiss Air Force, and was now working at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. The duo officially announced their project in 2003. After building and testing Solar Impulse 1, a prototype, they constructed Solar Impulse 2, optimised for long-distance flight, reduced energy consumption and improved performance. From the carbon fibre and other materials required for this ultra-lightweight plane, to the electronics necessary to create its super-efficient motors, every tiny component had to be optimised to the limit. The final product was the fruit of the efforts of a core team of 150 people, 80 partners and 80 companies, including Solvay, Omega, Schindler and ABB.

Solar Impulse 2’s delicate wings and fuselage were covered with 17,248 photovoltaic solar cells, each roughly the thickness of a human hair. These cells could absorb sunlight and charge the plane’s four highly efficient lithium-ion batteries. While the aircraft’s ability to fly while the sun shone was undoubted, its batteries had to store enough energy to keep the four propellers spinning through the dark night-time hours. The flight profile was tailored accordingly – climbing to around 8,500 m during the day and collecting as much solar energy as possible, and then gliding down to about 1,500 m during the night to conserve battery charge. In theory the plane could fly on forever in this manner. But the lone pilot obviously could not.

Solar Impulse 2 was incredibly light. Its wingspan of 71.9 m was only slightly less than that of an Airbus A380, the world’s largest passenger airliner. But while a fully-loaded A380 weighs around 575 tonnes, the carbon-fibre Solar Impulse 2 weighed only about 2.3 tonnes, or scarcely more than a sport utility vehicle (SUV). The aircraft’s wings could not be banked more than five degrees, otherwise it might spin out of control. Its cockpit was unpressurised. But it had advanced avionics, and a simple autopilot that allowed the pilot to steal cat naps. It also carried oxygen, permitting flight up to an altitude of 12,000 m. While it had a maximum speed of 140 km/h, it generally cruised at 90 km/h by day, reducing to 60 km/h at night to save power. It had no reserve fuel, so if the batteries malfunctioned or their charge were exhausted, the plane would be incapable of continuing.

Unlike the early aviation pioneering flights, this one needed a strong ground organisation. A mission control centre was established in Monaco using satellite links to gather real-time flight telemetry and remain in constant contact with the aircraft and its support team. The route was entirely in the Northern Hemisphere, eastward from Abu Dhabi. Mission control also predicted the weather and guided the aircraft through areas where it could absorb enough solar energy to survive the long night ahead. Since the plane was very vulnerable to adverse weather, the pilot had to wait patiently till good weather conditions were predicted along the route of each leg. Crossing the Pacific and Atlantic oceans took up to five days and nights. The longest of the 16 legs, an 8,924 km flight from Nagoya, Japan, to Hawaii, US, lasted nearly 118 hours. During this stage, Borschberg broke the absolute world record for the longest duration uninterrupted solo flight. It was just one of 19 official aviation records set during the journey. On these very long flights, the pilot could keep the plane flying on autopilot and take 20-minute naps. He would practise yoga and other exercises to promote blood flow and remain alert. His seat also served as a toilet seat.

However, extraordinary as the Solar Impulse 2 expedition was, in the end it showed that the prospect of pure solar-powered commercial aircraft is still remote.