INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

The insightful articles, inspiring narrations and analytical perspectives presented by the Editorial Team, establish an alluring connect with the reader. My compliments and best wishes to SP Guide Publications.

"Over the past 60 years, the growth of SP Guide Publications has mirrored the rising stature of Indian Navy. Its well-researched and informative magazines on Defence and Aerospace sector have served to shape an educated opinion of our military personnel, policy makers and the public alike. I wish SP's Publication team continued success, fair winds and following seas in all future endeavour!"

Since, its inception in 1964, SP Guide Publications has consistently demonstrated commitment to high-quality journalism in the aerospace and defence sectors, earning a well-deserved reputation as Asia's largest media house in this domain. I wish SP Guide Publications continued success in its pursuit of excellence.

- The layered Air Defence systems that worked superbly, the key element of Operation Sindoor

- Operation Sindoor | Day 2 DGMOs Briefing

- Operation Sindoor: Resolute yet Restrained

- India's Operation Sindoor Sends a Clear Message to Terror and the World – ‘ZERO TOLERANCE’

- Japan and India set forth a defence cooperation consultancy framework, talks on tank and jet engines

Sustainable Aviation Fuel a Special Report

Both Airbus and Boeing are in the process of developing aircraft technologically compatible with 100 per cent SAF. Numerous demonstration flights have been conducted to show that burning “neat” SAF is possible without compromising safety.

Many people perhaps feel that the danger of catastrophic and irreversible climate change caused by global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is something comfortably remote. It may happen in the distant future – perhaps around the turn of the century – and by then science would probably find viable solutions and avert any crisis. However, according to a new update issued by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in May 2023, there is a 66 per cent chance that the annual average near-surface global temperature between 2023 and 2027 will be more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels for at least one year. The temperature could again drop from that peak, but that is cold comfort. Climate scientists believe that a rise of 1.5°C is a climate change red line and overshooting it even for a few years is risky. It may trigger tipping points that cannot be uncrossed – such as the melting of permafrost that would, in turn, release vast amounts of trapped CO2 and intensify global warming.

The aviation industry is also acutely aware that although it is not a major emitter of GHG its share of global emissions will rise steeply in tandem with traffic growth. By the end of 2023 the global commercial aviation fleet could reach an all-time high of 28,000 planes and Boeing estimates that the number of aircraft would balloon to around 47,000 by 2040. For these tens of thousands of airliners to keep burning fossil fuel and spewing CO2 into the atmosphere is clearly unsustainable.

Sustainable aviation has therefore become something of a buzz phrase in recent years. Consequently, in 2021, member airlines of the International Air Transport Association (IATA) committed to achieve net zero carbon emissions from their operations by 2050. Besides new aircraft technologies, more efficient operations, direct carbon capture (DCC) and credible offsetting schemes, the main hope of making aviation sustainable rests on sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). Indeed, as much as 65 per cent of the reduction of GHG emissions required to attain IATA’s challenging net zero goal is expected to come from SAF.

WHAT IS SAF?

SAF is an umbrella term for all aviation fuels produced without the use of fossil energy. The term “sustainable” highlights the fact that the production process does not have a detrimental impact on the environment, since it involves neither deforestation nor land use change, nor does it require large amounts of fresh water. It also implies that the feedstock is obtained by focusing on waste-to-fuel and power-to-liquid (PtL) solutions, not by grabbing arable land from farmers. By design, SAFs are “drop-in” fuels that can be directly blended into existing airport infrastructure and are fully compatible with modern airliners.

SAF TECHNOLOGIES

A common misconception is that SAF is one particular type of fuel. In fact, SAFs can be produced from a variety of feedstocks (42 at last count) and through several different technologies, each with its own set of challenges. As of April 2023, nine conversion processes for SAF production have been approved and eight others are under evaluation by ASTM International. Researchers are continuously developing and refining new ways to create SAF and to produce it at lower cost from an expanding set of technologies and feedstocks.

- First Generation SAFs: These are the cheapest, simplest to produce and hence most commonly available type. They come from fats, oils and greases (FOGs). They reduce CO2 emissions by 50 to 80 per cent compared to normal jet fuel over the lifecycle of the product. The obvious problem is limited availability of feedstocks which prevents significant scaling up of production.

- Second Generation SAFs: These types of SAF are obtained from biomass and municipal solid waste and can potentially reduce GHG emissions by 85 to 95 per cent over their lifecycle. Biomass may include algae, crop residues, animal waste, sludge and forestry residue. However, production often requires advanced technologies and complex processes, such as thermochemical or biochemical conversion, that can be rather expensive and energy-intensive.

PtL – THE NEXT GENERATION

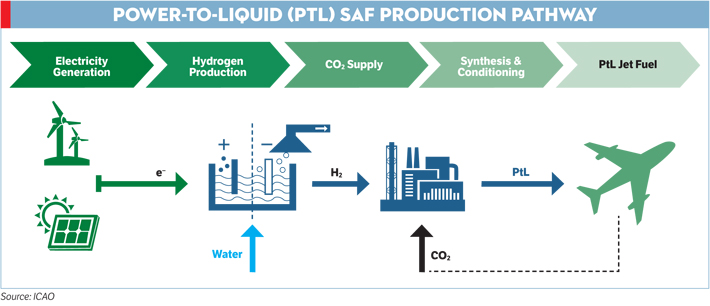

The most promising technology for SAF, albeit currently the most expensive, is PtL. PtL SAF involves the production of synthetic liquid hydrocarbon fuel using green hydrogen and non-fossil CO2 as the main feedstocks. This SAF process can potentially reduce GHG emissions by as much as 99 per cent especially if it uses CO2 obtained by direct air capture (DAC) and green hydrogen produced through electrolysis using renewable electricity. With a practically infinite supply of CO2 as feedstock, progress can be made towards a circular carbon economy. PtL processes vary. But all have in common the creation of a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide, known as syngas. At appropriate temperatures and pressures, syngas can be processed to yield hydrocarbons and water through the Fischer-Tropsch process.

In November 2021, in a world-first, an Ikarus C42 microlight aircraft flown by an RAF pilot completed a short flight in the UK powered entirely by synthetic fuel. Zero Petroleum’s UL91 fuel is manufactured by extracting hydrogen from water and carbon from atmospheric CO2. Using energy generated from renewable sources like wind or solar, these are combined to create the synthetic fuel.

In February 2023, SAF developer Air Company was awarded a contract by the US Air Force (USAF) to install its technology at various USAF bases. According to the USAF, Airmade SAF is the first fuel made entirely from CO2 emissions that matches the properties and performance of jet A-1 fuel, including aromatics. The fuel is net carbon neutral requiring as much captured carbon input as is emitted when it is burned. Therefore, instead of increasing emissions, it is recycling them.

FOR AND AGAINST SAF

Some of the key benefits of SAF (to use the singular term for all aviation fuels produced without the use of fossil-energy sources) are:

- SAF can be readily blended with normal jet fuel and potentially fully replace it.

- It generates up to 80 per cent less CO2 during its lifecycle.

- SAF also emits much less particulate matter and sulphur compounds that otherwise contribute to contrail formation and other climate change impacts.

- It has a higher energy density than normal jet fuel.

- Neither aircraft nor airports need to be redesigned.

- SAF can help farmers and the community by using waste from farms and landfills to produce fuel.

On the other hand SAF has its share of critics who cite its many disadvantages:

- SAF can be up to five times as costly as normal fuel.

- Since it releases CO2 into the atmosphere, like fossil fuel, it still contributes significantly to climate change.

- With many industries scrambling to obtain the same limited feedstocks, the aviation industry’s frenzied pursuit of SAF may deprive those more in need.

- Feedstock from food fats will be quickly exhausted, raising food prices and, threatening forests and farmland. For instance, there are growing suspicions that countries like China and Malaysia are passing off virgin palm oil – grown on plantations that contribute to tropical deforestation – as “used cooking oil” for SAF production.

PRODUCTION PAINS

In September 2021, the US government released a comprehensive strategy to accelerate the domestic production of SAF, initially to deliver 3 billion gallons per year by 2030 and 35 billion gallons by 2050. Its “Flight Plan for Sustainable Aviation Fuel” roadmap sets out a framework for the “SAF Grand Challenge”, a collaboration between multiple government agencies and the aviation industry to expedite decarbonisation of America’s aviation industry. The roadmap estimates a 600-fold increase in SAF production by 2030 compared to 2021, with a need for more than 400 bio-refineries and 1 billion tonnes of biomass or gaseous CO2 feedstock to meet 2050’s goal.

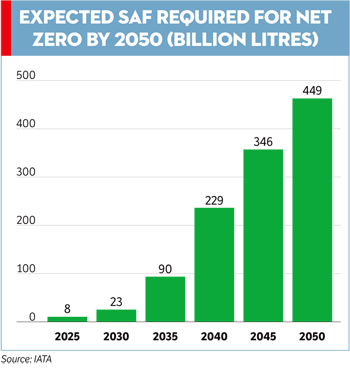

At present several airlines are racing to secure access to SAF to meet their own needs but also as a hedge against supply mandates in Europe and many other countries expected from 2025 onwards. However, the US assessment gives an idea of the scale of the problem ahead. Annual global SAF production that was just 538 million litres in 2022 needs to be boosted to 449 billion litres by 2050 (see graphic) in order to meet IATA’s net zero goal. This could perhaps be likened to a novice mountaineer still at base camp but aspiring to scale Mount Everest. It is difficult to imagine when and where the thousands of bio-refineries, renewable power plants and green hydrogen, carbon capture and other SAF facilities will be established, or who will make the mammoth investments required.

INDIA’S INITIATIVE

In May 2023, Hardeep Singh Puri, Union Minister of Petroleum and Natural Gas, said that India plans to mandate the use of one per cent SAF for domestic airlines by 2025. The reason for this rather modest blending target is the limited availability of SAF in the country.

However, with the global demand for SAF likely to skyrocket in the next few years India too can make an impact in the market. Municipal solid waste as feedstock is plentiful and the country currently has no environmentally friendly way of dealing with it. Similarly agro and forestry waste is abundant provided a system can be worked out to collect and use it productively. The government needs to establish a proper roadmap and economic incentives for SAF production so as to cash in on this golden opportunity to produce and perhaps export SAF. It would also help India meet its commitment of net zero carbon emissions by 2070.

NEAT AND ATTRACTIVE

SAF cannot be seen as an instant route to aviation’s environmental sustainability. One crucial requirement for its use to spread globally is the development of suitable standards to allow any type of SAF to be used interchangeably on any commercial aircraft anywhere in the world – much like normal jet fuel at present.

Linked with this is the issue of permitting the use of 100 per cent or “neat” SAF – an essential if the industry is to meet its long-term climate goals. Both Airbus and Boeing are in the process of developing aircraft technologically compatible with 100 per cent SAF. Numerous demonstration flights have been conducted to show that burning “neat” SAF is possible without compromising safety.

However, airlines that typically operate on very low margins are unlikely to find SAF appealing unless costs drop. Government intervention is essential to make SAF more attractive. Otherwise, there is a significant risk that global SAF production will fall short of the requirement. PtL SAF especially needs to be encouraged despite its high cost, since it is perhaps the most environmentally sustainable in the long run. Some analysts believe that SAF is unlikely ever to equal the price of jet fuel, which means increased fares are inevitable. This is not a prospect that will appeal either to the airline industry or to passengers but it may have to be faced sooner rather than later if the global transition to SAF is to gain momentum.