INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

The insightful articles, inspiring narrations and analytical perspectives presented by the Editorial Team, establish an alluring connect with the reader. My compliments and best wishes to SP Guide Publications.

"Over the past 60 years, the growth of SP Guide Publications has mirrored the rising stature of Indian Navy. Its well-researched and informative magazines on Defence and Aerospace sector have served to shape an educated opinion of our military personnel, policy makers and the public alike. I wish SP's Publication team continued success, fair winds and following seas in all future endeavour!"

Since, its inception in 1964, SP Guide Publications has consistently demonstrated commitment to high-quality journalism in the aerospace and defence sectors, earning a well-deserved reputation as Asia's largest media house in this domain. I wish SP Guide Publications continued success in its pursuit of excellence.

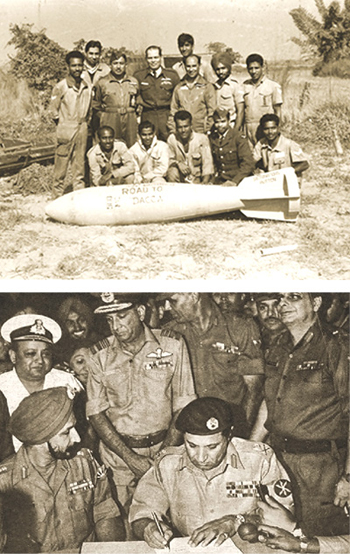

Indo-Pak War 1971 - Victory Revisited

Thanks to the superb use of air power by the IAF, the Indo-Pak War 1971 was the first time India successfully fought a two-front war. The war concluded on December 16, 1971, with the birth of Bangladesh from the ashes of East Pakistan. As Bangladesh celebrates 40 years of existence, Air Marshal (Retd) V.K. Bhatia revisits one of India’s rarest ‘victories’ since independence.

“I speak to you at a moment of great peril to our country and our people. Some hours ago, soon after 5.30 p.m. on the 3rd December, Pakistan had launched a full scale war against us...Today a war in Bangladesh has become a war on India...I have no doubt that by the united will of the people, the wanton and unprovoked aggression of Pakistan should be decisively and finally repelled...Aggression must be met and the people of India will meet it with fortitude, determination, discipline and utmost unity.”

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi,

December 3, 1971

On the evening of December 3, 1971, as the Indian Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, was returning to Delhi from Calcutta on board an Air HQ Communication Squadron aircraft the pilot came up to her Principal Adviser D.P. Dhar and asked him to come to the cockpit as there was an urgent message from Delhi. Dhar spent about three to four minutes in the cockpit, came out and spoke to Gandhi, walked back to his seat and turned to those sitting behind him and said, “The fool has done exactly what one had expected.” And this officially started the third round of military confrontation between the two nations—India and Pakistan— since their creation by the British in 1947. However, the 1971 war was not due to Pakistan’s inane desire to annex Kashmir by force. This time, the Pak President and Martial Law Administrator, General Yahya declared war against India to teach it a lesson as it was seen to be meddling in Pakistan’s internal affairs. This is exactly what India was hoping for to be able to overtly start a military campaign in East Pakistan in aid of the Mukti Bahini liberation force. But what started as somewhat conservative military objectives in the East quickly turned into a military blitzkrieg—thanks to the Indian Air Force (IAF)—resulting in the liberation of Dhaka within 14 days and the creation of a brand-new nation. Bangladesh rose from the ashes of East Pakistan where the fire was lit by none other than the West Pakistan’s political and military establishment. However, none of this may have been possible but for the superb use of air power to spearhead and support military operations on the ground, within the available diplomatically constrained timeframe. This was also the first time India successfully fought a twofront war— once again, thanks to the IAF and its innovative use of air power. But first: a redux into history which led to the ‘third round’.

Events Leading to the War

As a backlash to the violent crackdown by West Pakistan forces led to East Pakistan declaring its independence as the state of Bangladesh and to the start of civil war. The war led to a sea of refugees (estimated at the time to be about 10 million) inundating the eastern provinces of India. Facing a mounting humanitarian and economic crisis, India was forced to take up the issue with the international community to stop Pakistan committing the horrible genocide of its own population in its eastern wing. However, the lukewarm response of the international community soon made it apparent that India would have to deal with the problem on her own. Pakistan’s belligerent attitude also made it clear that once again, India’s bellicose neighbour was spoiling for a fight. From March 1971, the writing was on the wall, and the Indian Cabinet gave orders to the armed forces to prepare for war. This was also the time India started to train the ‘Mukti Bahini’, eventually close to a 1,00,000 strong force of the Bengali liberation force to fight for its rights in East Pakistan. Finally, in the face of a belligerent neighbour, it was no longer a question of ‘if’, but ‘when’ the country would go to war. In November, intelligence reports indicated that Pakistan would strike the first blow. Rather than taking the initiative and being branded as the aggressor, India chose to wait. It did not have to wait too long.

As the situation in the east kept deteriorating and Pakistan mobilised its forces in the west, in October 1971, India laid down the following limited objectives for its possible military operations:

- To assist the Mukti Bahini in liberating a part of Bangladesh, where the refugees could be sent to live under their own Bangladesh Government.

- To prevent Pakistan from capturing any Indian territory of consequence in Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab, Rajasthan or Gujarat. This was to be achieved by offensive defence and not merely passive line-holding.

- To defend the integrity of India from a Chinese attack in the north.

It is clear that to start with, the capture of Dhaka was not one of the aims of the war. In fact, no regular formation had been assigned a role to capture Dhaka. The maximum change that seems to have taken place was to define the extent of the “part of Bangladesh” to the area bounded by the rivers Jamuna-Padma-Meghana which enclose the Dhaka ‘bowl’. But the fact that the IAF was able to achieve complete air supremacy in the East in the first two-three days of the war allowed uninterrupted and totally secure land and air support operations—a modern day blitzkrieg which finally resulted in the total collapse of the politico-military establishment, making way for the unconditional surrender of the military regime and capture of Dhaka.

Lessons of 1965 Indo-Pak War

At the individual service level, there were many lessons for the IAF in the 1965 Indo-Pak war which warranted urgent corrective actions to be taken. It goes to the credit of the IAF that it had done its homework well and was fully prepared for the war when it came. The shameful loss of nearly 40 aircraft on the ground due to enemy air action during the 1965 war had galvanised the IAF to create hardened covered aircraft shelters (concrete blast pens) at its operational bases. The move paid rich dividends during the war with the IAF losing only three aircraft on the ground due to enemy air action and that too because these aircraft were taxiing in/out from their pens for operational missions. This was a total reversal from the earlier war as this time Pakistan Air Force (PAF) was on the receiving end losing a large number of aircraft to our counter-strike missions. But there were other reasons too which contributed to the PAF reverses.

A major shift in IAF strategy was brought about by the lessons learnt in 1965. Till then, the air force strategy was based on the Royal Air Force philosophy emanating from the Second World War, which placed the principal emphasis on the bomber as the primary instrument of offensive air power with the fighter being seen as essentially a defensive component. For the 1971 war, the IAF had fully incorporated the strategy of meaningful counter-air strikes against the PAF bases in both western and eastern theatres a bulk of which was carried out by fighter aircraft. Canberra light bombers were utilised largely for night bombing only. To achieve greater accuracy, a special unit, Tactics & Air Combat Development Establishment (TACDE) had been raised at Ambala and specially trained to carry out night strike missions against PAF airfields in addition to the night strikes by bombers. To a considerable extent, the unit was used for this purpose on the western front in the first twothree nights of the war.

On the inter-services synergy front, though still not institutionalised even after serious deficiencies exposed during the 1965 War, the three service Chiefs did manage to create a far greater level of synergy through personal maturity and cooperation. At the operational level, the entire organisation in support of the Army was rehashed and strengthened through inter-service cooperation. Advanced HQs of Western Air Command (WAC) and Eastern Air Command (EAC) were set up alongside their respective Army Commands. These were tasked with providing support to the Army as required. Learning from 1965, the organisation was extended further down the line, and each Corps HQ under the Western and Eastern Army had a Tactical Air Centre (TAC), with Forward Air Controllers (FACs) deployed in the field down to the Brigade level for guiding incoming air strikes onto their targets in the tactical battle area (TBA). In 1965, only the Advanced HQ of WAC was in existence, without any mechanism for vetting demands for air support or assigning any priority. In order to best meet the requirements of the Army, the IAF had earmarked specific squadrons for particular types of tactical support to specific areas. In the east, 60 per cent of IAF effort was initially allocated to close air support. Following the total neutralisation of the PAF in that sector, the entire air effort was diverted to that task. These details were known down to the level of the TACs and even the FACs. These measures paid off and were a great improvement over the comparatively inefficient Joint Army Air Operations Centre (JAAOC) functioning in 1965.

IAF strategy, put into effect in the west in 1971, was based on a three-tiered ‘target system’ evolved by Air Headquarters. The first involved the use of fighters for ‘Air Defence’ as well as ‘counter air’ tasks along with attacks by fighter-bomber and bomber aircraft. The effectiveness with which this was pursued is borne out by the fact that there was little or no interference by the PAF on Indian land or naval forces in most sectors. The second tier involved hitting the enemy’s energy systems, including the oil storage tanks at Karachi, the Sui Gas Plant in Sind, the Attock Oil Refinery and power stations such as the Mangla Hydroelectric power plant in Punjab. The third element to be targeted by the IAF was the road and rail transport network in West Pakistan.