INDIAN ARMED FORCES CHIEFS ON OUR RELENTLESS AND FOCUSED PUBLISHING EFFORTS

The insightful articles, inspiring narrations and analytical perspectives presented by the Editorial Team, establish an alluring connect with the reader. My compliments and best wishes to SP Guide Publications.

"Over the past 60 years, the growth of SP Guide Publications has mirrored the rising stature of Indian Navy. Its well-researched and informative magazines on Defence and Aerospace sector have served to shape an educated opinion of our military personnel, policy makers and the public alike. I wish SP's Publication team continued success, fair winds and following seas in all future endeavour!"

Since, its inception in 1964, SP Guide Publications has consistently demonstrated commitment to high-quality journalism in the aerospace and defence sectors, earning a well-deserved reputation as Asia's largest media house in this domain. I wish SP Guide Publications continued success in its pursuit of excellence.

- The layered Air Defence systems that worked superbly, the key element of Operation Sindoor

- Operation Sindoor | Day 2 DGMOs Briefing

- Operation Sindoor: Resolute yet Restrained

- India's Operation Sindoor Sends a Clear Message to Terror and the World – ‘ZERO TOLERANCE’

- Japan and India set forth a defence cooperation consultancy framework, talks on tank and jet engines

Fight over Slots

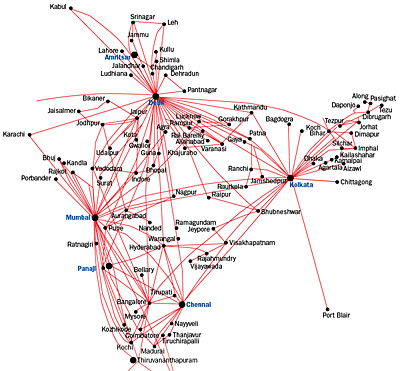

The tussle between airlines and the MoCA over route networking is a continual process. One of the solutions lies in improving the infrastructure at the smaller airports to a level that airlines find flying to them attractive.

In May 1953, the Government of India nationalised the airline industry with the enactment of the Air Corporations Act, 1953, established two air corporations, Indian Airlines Corporation and Air India International, and transferred the assets of all the then existing airlines (total nine) to the two new entities. The operation of all scheduled air transport services from, to and across India was made a monopoly of these two corporations. This monopoly ended in 1994 with the repeal of the Air Corporation Act; the domestic air transport services were liberalised and private operators were permitted to provide scheduled air transport services. The initial cackle of variegated geese that took wing in the Indian skies as a result almost vanished in an implosion for various reasons by the end of the 1990s. A second wave started in 2003 with Air Deccan and continues a blood-spattered struggle even as we read this. The government’s well intentioned policy framework for an orderly growth of air transport services has pain points for the airline industry; and one of them is route networking.

The route network (the airports it connects) of an airline depends on “slots” and route dispersal guidelines (RDGs). Slots relate to permission from the airport operator for arrival and departure time slots (and by inference, night parking slots). In case of the airports managed by the Airports Authority of India (AAI), it is the AAI which allocates the slots. For airports not managed by AAI, the slots are allocated by the concerned airport operator in coordination with AAI. All domestic airlines who want to operate at an airport, file for arrival and departure slots with the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) and the respective airport operators such as AAI, Indian Air Force, Indian Navy and private operators in airports like Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore, Hyderabad and Cochin airports. The slot requests are analysed vis-à-vis airport capacity parameters such as runways, aprons and terminal buildings. Based on the analysis, all airport operators either approve the slots requested in respect of their airports or generate a list of alternative offers. These approved and offered slots are discussed in a meeting wherein all the airlines, the DGCA, the Bureau of Civil Aviation Security (BCAS) and the airport operators are present. After the meeting often involving animated horse-trading, the approved slots are conveyed to DGCA for approval of the flight schedule. Slots are allocated twice a year, for summer season and winter season; each season being a period of six months. Allocation of slots is based on “Grandfather Rights” and “use it or lose it” rule in case of mergers and acquisitions of domestic airlines. Grandfather rights means that the slots allocated to a particular carrier in the previous season are reverted to the same carrier. This policy accounts for allocation of a large majority of slots, particularly at peak times. In the context of mergers, according to the domestic air transport policy, the airline which is merging with or acquiring another airline is allowed to take control of the airport infrastructure, including slots of the latter. “Use it or lose it” rule implies that this right will be available with the airline that takes over till such time as the rights are under use. If the concerned rights are not used, the airline stands to lose the user rights over them. As per the slot allocation policy, after allocation of slots on the basis of “grandfather rights” and “use it or lose it” policy; 50 per cent of the left over slots are allotted to the new airlines. There are no charges for peak and non-peak slots in the policy but this entry barrier is particularly significant for new airlines which find it difficult to capture peak hour slots, as those are rarely abdicated by the large players in the market.

RDG have been in existence since 1994, but have been tweaked a little every two or three years and especially since 2003. One of the laudable objectives of the RDG is to provide connectivity to smaller cities and towns, or in other words, to boost regional aviation. As airlines tend to crave for metro slots, the routes they tend to fly also get biased towards metroto-metro connectivity. It is easy for anyone to see that there is not much “carrot” that can be brandished in favour of the smaller airports. Therefore, the government has been forced to use a “stick” – the RDG that mandate domestic airlines to fly a proportion of their total flying capacity over unviable and unattractive routes connecting cities/towns in the North-eastern Region (NER), Jammu & Kashmir (J&K), Andaman & Nicobar Islands (A&NI) and Lakshadweep. The capacity of an airline for this purpose is measured in available seat kilometres (ASKM), which is the sum of the products obtained by multiplying the number of passenger seats available for sale on each flight stage by the corresponding stage distance. Routes have been classified into four categories according to these guidelines, namely, Category I, Category II, Category IIA and Category III. Any airline operating service on one or more of the routes under Category I (routes connecting metro-tometro) is required to provide such service in Category II (NER, J&K, A&NI and Lakshadweep to the rest of the country) to the extent of a minimum of 10 per cent of the ASKMs as deployed in Category I. Further, a minimum of 10 per cent of the ASKMs as deployed in Category II is required to be deployed in Category IIA (one Category II airport to another) and a minimum of 50 per cent of ASKMs deployed in Category I is required to be deployed in Category III (the rest of the airports i.e. other than Category I and Category II).